Brain Circulation

Is American pedagogy stifling the participation of Chinese students?

By Steve Weiland

“Yidong” by Claire Chien (licensed through shutterstock).

Whatever the problems facing American higher education—equity in admissions, student debt, the impact of the culture wars on the curriculum, the management of free speech—the U.S. still leads the world in attracting international students, particularly from China.

Enrollments of Chinese students climbed from a little under 10,000 in 2005 to 372,000 in 2020. Post-COVID, the numbers have dropped some—in 2023, enrollment was down to 290,000—but the population of Chinese students studying here has remained significant, coming to about one-quarter of all international students in America. The phenomenon has been celebrated as a sign of the globalization of our postsecondary system, with (presumably) gains in cosmopolitanism for American students. Higher ed administrators haven’t minded what the influx has contributed to institutional budgets.

Competing “initiatives” display the paradox of educational relations between Chinese and U.S. institutions. In 2022, the Chinese Historical Society of New England launched a multi-year project to celebrate the 150th anniversary of Chinese students attending American colleges and universities. But just a few years earlier, the U.S. Department of Justice, in keeping with the interests of the Trump administration, had the National Institutes of Health and other agencies require universities receiving grants to investigate participating Chinese faculty members (many of whom had earned American undergraduate and graduate degrees) for suspicious elements of their work that might benefit their home nation. Nearly fifty scientists lost their posts as a result. In reporting the story in March 2024, the Washington Post concluded that some Chinese graduates and current visiting students are warning that “the United States is losing its luster.”

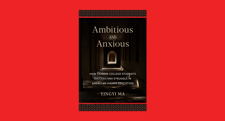

Published just before the pandemic, Yingyi Ma’s Ambitious and Anxious: How Chinese College students Succeed and Struggle in American Higher Education (Columbia University Press, 2020), probes what has prompted Chinese families to accept the substantial expense of sending their children abroad to a nominal political and economic enemy. A sociologist at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, Ma explains that the U.S. gained its influence in China as an educational destination largely through America’s domination of global institutional rankings.

Basing her findings on an impressive combination of survey data, interviews, and considerable time on the ground at Chinese and American institutions, Ma finds that, for many Chinese students, studying in the U.S. is a respite from the national exam-based system, the centuries old “Gaokao,” that shapes local schools and individual prospects for higher education and civil service careers. Enrollment in U.S. institutions with high international rankings has also satisfied the desire of Chinese students and their families for greater social status. Indeed, Ma names the ambition for an American degree the “New Education Gospel” in China. It has been sustained as a subculture reflecting the new wealth and cosmopolitanism of many Chinese families, particularly in large cities, and the wish to gain the rewards of a globalized economy.

Alas, according to Ma, the rewards come with unwelcome limits. For Chinese students at U.S institutions, large and small, “What remains masked by their economic privilege and transnational mobility is the relative loss of social status and cultural capital after arriving in the United States. From academic studies to social integration, student marginalization is palpable, leading to much anxiety.”

Chinese students have a hard time breaking into campus cultures. Seeing themselves as more diligent than their American counterparts, many reject the “party school” atmospheres they find. Their “pragmatic collectivism,” inspired by growing up in China, is hard to join to the “expressive individualism” they encounter among Americans. Ma names their campus strategy “protective segregation.”

Current American pedagogical trends toward “active learning” also turn out to be problematic for Chinese students. In a sharply written chapter dedicated to “participation” (or “engagement,” as our pedagogical reformers put it), Ma explains why it is so difficult for Chinese students to speak up in class, to give and take with instructors and other students.

There is, of course, the problem of mastering a new language. But even a large share of those who see themselves as capable in English find it hard to accept the rewarded practices of classroom speech. They may welcome the principles of heterodoxy as counterpoint to the traditional Chinese classroom. But contributing to viewpoint diversity and constructive disagreement taxes their resources for participation.

Being an “active” learner in a U.S. classroom requires speech based on taking a (sometimes fact-free) position and questioning the views of others. But Chinese students bring with them cultural and classroom habits of reticence in groups and deference to authority; Ma notes powerful Confucian traditions that feature, in teaching and learning, “rumination and contemplation, not elaborate verbal exchange.” Finding a place for each cultural style is a demanding task for professors.

Independent and pluralistic thinking—intellectual habits Chinese students may encounter in the U.S.—and the activism that often follows do not appear to tempt most visiting Chinese students. Ma notes, “The Chinese government has been pursuing and promoting social harmony and stability in the face of various kinds of social tensions and injustices in its fast-changing society. The last thing it wants is to nurture a form of education that promotes outrage and, thus, potential instability.” A recent Washington Post investigative report documented the long-reach of the Chinese government, as demonstrators in San Francisco protesting Beijing’s policies and a visit from Chinese leader Xi Jinping were met by organized thugs who harassed and silenced them, including through brutal violence.

Adding to the tensions Chinese students must feel, politics in the U.S. is now framed by attitudes toward immigration, casting a shadow over Chinese students hoping to come here. Still, as little as a few years ago, Ma saw students describing fresh advantages to studying in the U.S. A popular formulation of the asymmetry in international education, sometimes applied to the results of China’s “New Education Gospel,” contrasts the “brain drain” with “brain gain.”

Ma’s study convinced her of a third way: “Many Chinese students are interested in engaging in brain circulation—keeping and developing their networks and careers in both home country and host country—and returning to China does not prevent them from achieving that goal.” It is, she says, a sign of “how empowered they feel in this globalized world.”