A Field Guide to Epidemiology

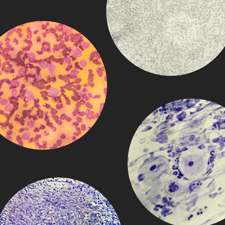

Above the skin, below the skin.

By Nigel Paneth

Photo-illustration by Janelle Delia using photos licensed through shutterstock.

When people think of epidemiologists, they probably have in mind the good people employed in county or state health departments and federal agencies like the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) who do what we like to call “shoe-leather” epidemiology. These public-service epidemiologists are the ones who get called when a dozen people who attended the same church supper develop severe diarrhea. “Shoe leather” because they pound the streets, knock on doors, interview people, inspect kitchens, and—in the end—determine that the potato salad was contaminated with Salmonella.

Trained in biology, mathematics, sociology, and a few nearly unique methodologies, epidemiologists often go beyond isolating the cause of a local outbreak, because epidemics are not just about infectious diseases but about every kind of health adversity that occurs more often than it should. Epidemiologists taught us—against resistance from many in medicine and everyone in the tobacco industry—that the lung cancer epidemic was a consequence of the cigarette smoking habit that largely took root in the U.S. after WWI, reaching its peak in the 1950’s, with the wave of deaths following about 30 years later.

Academic epidemiology is where the broader scope of epidemiologic investigation sees its development, with a range of sub-disciplines defined by disorders of public health interest (cancer, heart disease, stroke, auto-immune disorders, problems of pregnancy and birth) or defined by the factors (we like to call them exposures) that influence health and disease, such as nutrition, environmental chemicals, infectious agents and social circumstances. Some epidemiologists work closely on the border with our cousins the biostatisticians, advancing methodology. Others, and I include myself here, find themselves closer to the biological or biomedical roots of our profession, tied more to disease processes.

In our field, we sometimes speak of exposures as being either above or below the skin. Above-the-skin epidemiology considers all exposures from the outside—from microbes to poverty—that affect risk of disease, while the principal below-the-skin form of epidemiology is gene-wide association studies, the attempt to link human genetic variants to disease processes or responses to treatment. The popularity of these various approaches is reflected in NIH funding patterns, which since the Human Genome Project’s beginnings have been quite generous to genetic epidemiology.

While all epidemiologists have in common an interest in the causes of disease and health outcomes, our discipline is not without its tensions.

The first is whether we are a purely intellectual discipline doing science for its own sake or a more purposive pursuit, with the goal of improving public health as its hoped-for end product. Supporters of the more purist view have bandied about “neutral” terms for our field; “occurrence research” was one suggestion. One of our journals briefly tried to ban discussion sections that addressed “public health implications” of epidemiologic findings. But these efforts faded quickly.

We must take account of not just the frequency of diseases and their causes, but of human wants, habits, and prejudices.

We cannot easily extricate our methods and terminology from the measurement of the impact of disease or from study designs and analyses that focus on disease control, because our data will inevitably be used to shape public health policy. And epidemiologists often play a more direct role by making health policy recommendations, which is no simple task but must take account of not just the frequency of diseases and their causes, but of human wants, habits, and prejudices.

A second tension centers on the fact that, although epidemiologists are by nature skeptics who require the makers of assertions and claims to have their feet held to the fire, advocacy can sometimes elbow its way in. This has happened in some corners of environmental epidemiology, for example, where disputes over the impact of certain chemical exposures have become quite intense. But these tensions might be viewed as poles of the epidemiologic globe—from purely theoretical epidemiology to intense advocacy—and, as usual in disciplines, most practitioners live somewhere near the equator.

That said, there is the anti-science aura that hovers around universities, at times linked to a vision of science as Western and thus colonial. An undergraduate at my annual lecture on smallpox eradication was taught in an anthropology course that the British introduction of vaccination to India had displaced “traditional vaccination practices,” thereby harming health.

What the anthropology professor neglected to mention (or perhaps did not know) was that it was the practice of inoculation—intentional artificial exposure to smallpox aimed at inducing what we now know is immunity— that had been displaced by vaccination. Known throughout much of the ancient world from China to Africa, inoculation was used as a reasonably effective preventative procedure, but with a far from trivial risk of producing lethal smallpox itself, making vaccination, which can never cause smallpox, clearly superior. (Ironically enough, inoculation was introduced into England from Turkey.)

Whether coming from the far left or right, the anti-science miasma now polluting the political atmosphere has serious ramifications for epidemiology, a profession whose views, and the policies derived from them, are very much in the public eye. During the deadly heights of the COVID-19 pandemic, most epidemiologists favored population-level attempts to control the epidemic, including masking, isolating, vaccinating, and the like. A very small minority allied itself with the libertarian approach of letting the epidemic take its course until we reached “herd immunity,” regardless of the casualties incurred.

Whether coming from the far left or right, the anti-science miasma now polluting the political atmosphere has serious ramifications for epidemiology.

Sweden—whose public health authorities shunned mitigating strategies—experienced double the COVID mortality rates of neighboring Denmark and Norway, countries that enforced policies designed to reduce transmission. In the U.S., these mitigating policies generated intense political divisions and considerable animosity to epidemiologists and other public health workers who were just trying their best to save people from dying from COVID and overwhelmed health systems.

It is disorienting to live in a time when immunizations—viewed as unquestionably good for most of the 20th century—are under assault in some quarters. If diphtheria were still at its late-nineteenth-century level, we would lose more than a third of a million children every year to a disease whose usual manner of dying—slow, steady, strangulation—is about as awful as can be imagined. Photos of polio-stricken children in iron lungs are relics of an ancient world. Yet the complete eradication of smallpox— which killed a million a year in the 1950’s—by vaccination is now just an “alternative fact.” Unfortunately, epidemiology must deal with the vagaries of human nature both in the diseases it studies and in the attempts it makes to address them.