A Field Guide to Legal Anthropology

Anthropologists think we’re lawyers. Lawyers think we’re anthropologists.

By Deepa Das Acevedo

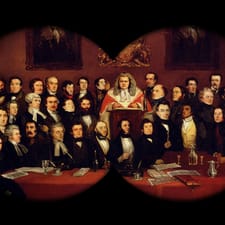

"The Judge And Jury Society In The Cider Cellar" by Archibald Henning, 1843. Public Domain.

What is legal anthropology? Ask three people and you’ll get five answers.

This is to be expected given the two parent disciplines involved. Anthropologists are chronically averse to definitions: we study culture — or cultures (note the artfully italicized plural) — but many of us disavow the very concept. Lawyers, meanwhile, find definitions powerfully addictive, which may explain why the U.S. Supreme Court quotes dictionaries more often than grade school essayists.

Small wonder, then, that the interdisciplinary child created by these two fields can’t even settle on a name (“legal anthropology” versus the “anthropology of law”), much less a central animating concern. Do we study law in context? Law across contexts? (Is there such a thing as law?)

Sir Henry Maine (d. 1888) is a decreasingly common originator. He has the virtues of having been a white male colonialist, which has allowed him to blend in nicely with the disciplinary forebearers that anthropologists must ritualistically bemoan. Other ancestors are no less male and mostly no less white, but their colonial credentials are varied. All of them walked and talked with “the natives” to discover if they, too, had law. Can you have law without states, law without judges — law without courts, or cases, or writing? For the most part, these early legal anthropologists decided that you can. “Law,” they decided, simply meant the rules that were used to resolve “cases.”

For nearly a century after Maine, legal anthropologists set about inventorying and comparing rules from around the world. At its best, this approach was stamp-collecting with a heart. It largely showed how “they” had “law” even if what they had looked nothing like our courts, our codes, and our judges. But it also doubled down on what Michel-Rolph Trouillot has called anthropology’s obsession with filling the savage slot — pursuing the exotic Other in faraway lands.

This rule-centered approach also failed to explain exactly how those Others went about their business without the courts, codes, and judges that “we” so heavily rely on to maintain social order. To account for the existence of order without rules, legal anthropology turned to studying dispute-resolving processes, reasoning that maybe processes were at the heart of this thing we like to call law.

Eventually, legal anthropologists concluded that “law” consisted of both rules and processes — and that, regardless of what law really was, they were tired of asking if everybody had it. In fact, by the 1980s, legal anthropologists seemingly grew tired of talking about anything too law-ish, because law, much like anthropology itself, was obviously an oppressor’s tool. (Never mind that many progressive icons were lawyers, too.)

At the end of the twentieth century and into the early years of the twenty-first, anthropologists largely worked as if legal technicalities were best left for lawyerly tradespeople, whether they were employed by law firms or law schools. Lawyers could remain fixated on formal law — on city ordinances, state regulations, national constitutions; on judicial opinions and on administrative rules. The Magic Eye of anthropology would look beyond the immediate realities to see the more interesting, underlying patterns.

Then a few of the tradespeople got Ph.D.s and a few doctorates went to trade school. Some more who fell into neither of these categories nevertheless found themselves housed in interdisciplinary “legal studies” departments where they encountered colleagues still interested in talking about law. And, over time, all of us have found each other.

What kinds of research do we produce?

Some examples: We show why the declining frequency of jury trials in the United States has not resulted in the declining influence of jurors. (As Anna Offit has noted, that’s partly because prosecutors rely heavily on imagined — and therefore often caricatured — jurors while crafting their litigation strategies.) We show why worker classifications that are widely panned for both their unfairness and their inefficiency are nevertheless so hard to dispense with. (As my own work has indicated, that’s partly because the employment classification system we love to hate rests on an understanding of freedom as negative liberty — “freedom from” — that is deeply compelling even for those it hurts.) Put simply, we show how cultivating attentiveness to the ideas and infrastructures of formal law can help us understand society.

The best among us are, I think, relearning a very old anthropological lesson: that “insider” (emic) knowledge matters at least as much as its “outsider” (etic) counterpart. Anthropology that uses anthropological categories to study power, justice, inequality, and so on, does important work — but it’s work that’s often unrecognizable to law folk, and even to ordinary people dealing with ordinary laws. Meanwhile, anthropology that takes seriously the categories, practices, systems, and rules that lawyers recognize and that all of us are subject to — however unevenly — well, that kind of legal anthropology stands apart because it actually has a chance of “making the familiar strange” in a world where nothing is truly strange anymore.

Being this kind of legal anthropologist is not unlike being a second-generation immigrant. Among anthropologists, we are considered lawyers (whether or not we are licensed to practice law); among lawyers, we are most definitely anthropologists. We can blend into both disciplines’ gatherings, but because there are usually more blazers among us than either suits or scarves, we are often either the most casually dressed lawyers or the most formally dressed anthropologists. And our command of disciplinary vernaculars is predictably uneven: my Anthropologese is as rusty as my Malayalam even though both are my mother-tongues and first languages.

Liminality, in other words, defines us. This should please our anthropological forebearers, since some of them — most notably Victor Turner — are responsible for popularizing that concept as applied to social interaction. The very promise of any definition should also make our lawyer-ancestors ecstatic — if only they could find an appropriately Bluebooked citation for it. For those of us who occupy this liminal state — whether by choice or necessity — the task of speaking across the aisle, in both directions, to each of our parent disciplines, is both the best and the hardest part of being a legal anthropologist.