And That’s How I Learned To Speak Up

The academy is no place for self-censorship

By Matthew Burgess

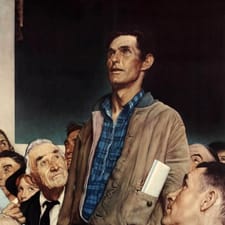

"Save freedom of speech. Buy war bonds." by Norman Rockwell, 1944. Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain.

Your integrity is your most precious asset, and no one controls it but you.

Speak up for what’s right, especially when it takes courage. Check your assumptions. Don’t be a bully; don’t pile on or kick someone who’s down. My parents instilled these principles in me throughout my childhood, and they have guided me throughout my life.

The first real test of these principles came when I was in high school in Quebec. An alumna spoke to our class about child labor in sweat shops overseas, and about how she and others were working to stop it through the organization Free the Children. Horrified and inspired, my friends and I immediately started an FTC chapter in our high school. We organized fundraisers and attended rallies about that issue and others.

Through FTC, I got invited to a national conference for Canadian youth social justice activists. Parts of the conference were inspiring, deepening my resolve to pursue a career that could make the world a better place. But parts also disillusioned me with some of the dominant ways of thinking in youth advocacy.

We were some of the country’s most ambitious youth, who were about to spend tens of thousands of dollars to go to college, presumably to learn something. Yet, we acted like we already knew everything. Naturally, we didn’t see the contradiction.

We talked about older generations with contempt, like they had wrecked the world by not caring, by not paying attention, or both. “If only more people listened to children” was the vibe—one I recognize in some of today’s climate change activism. But did we really think that little of our parents and our grandparents? Did we really think that little of our country’s leaders? I knew deep down I didn’t.

Many of our grandparents (including mine) had risked their lives fighting Nazism in their youth. Our parents’ and grandparents’ generations created the wealth and built the post-war institutions that have made the world a much more prosperous, safer and more peaceful place. They led movements for civil rights, women’s rights and environmental protection.

Careers, built over decades, are expensive and precious. Combating sexual harassment and racial discrimination honors that. But cancel culture doesn’t.

When I would press older members of my family on why the world wasn’t more socialist (as I thought it should be at the time), their response was never “because we don’t care about the poor.” Instead, they often asked good questions, like:

“How is the government going to pay for these things? How else, but with markets, do we maintain incentives for people to create the businesses and innovations that power prosperity? Why is it that communism has such a deadly track record?”

In other words, if you want to make the world a better place, check your assumptions. The world has serious problems. Take them seriously. Put in the work to understand them. Study what’s been tried in the past. If someone offers you an easy solution, ask yourself if they’re really just offering you a way to feel better about yourself.

Fast-forward to graduate school. By then, I was already more of a moderate than a social democrat, but I still shared many of the preoccupations of the left. The 2008 recession was a travesty, caused in large part by unchecked greed and hubris. The war in Iraq was a disaster. Climate change denial was harmful, funded by dark money, and getting in the way of common-sense solutions to the problem. Same-sex marriage rights were long overdue, and they were finally starting to feel winnable.

In academia, some degree of affirmative action for women and minorities was noticeable, but so was racism, sexism and sexual harassment. In the early days of DEI (diversity, equity and inclusion), it felt like we were genuinely trying to level the playing field, and we were trying to stop judging people by their immutable characteristics.

Then, during my postdoc years, as the Great Awokening got into full swing, things noticeably changed. The focus of DEI gradually seemed less about opposing stereotyping and reducing the importance of race and gender in who gets ahead and more about introducing new stereotypes, and increasing the importance of race and gender in who gets ahead.

Important efforts to crack down on workplace sexual harassment and hold serial sexual predators like Harvey Weinstein accountable gradually morphed into efforts to ruin careers over “microaggressions,” wrong-think or politically incorrect research. Social media pile-ons became common, sometimes with real-world consequences.

Careers, built over decades, are expensive and precious. Combating sexual harassment and racial discrimination honors that. But cancel culture doesn’t. It treats careers as cheap. It makes us more racist and sexist, not less. It also makes us hypocrites.

This hypocrisy extends to the principles of science. The tools of science—responsible for huge global advances in prosperity and health—are universal and belong to everyone. Diversity is good for science because people who think differently make each other smarter. If we exclude people from science because of characteristics unrelated to their merit, we might miss out on future Einsteins. Facts, like global warming, don’t care about your politics. These things are obviously true.

Yet, cancel culture, political monocultures enforced by litmus tests, and ever-expanding identity-based reward systems undermine these ideas. So, too, do notions that certain groups need to have their own “ways of knowing,” seemingly implying that the tools of science don’t, in fact, belong to everyone.

Hypocrisy also extends to the mantra that impact matters more than intent. If that is true, why did we seem more concerned with microaggressions in 2020 than we were with the thousands of deaths caused by post-George-Floyd police pullback? Why were we so uncurious about the devastating and unequal effects of long-term lockdowns and campaigns against school discipline on K-12 school performance?

Were we really checking our assumptions? Were we really doing what was right and acting with integrity? Were we really showing courage? Were we really opposing bullying? Did we not see how devastating these trends in academia could be to our public trust, reputation and funding in the long term? We are now finding out the hard way how much this loss of trust and reputation can cost.

When I raised these issues at the time with senior, tenured colleagues—those with the most job security, academic freedom and power—the gist of the response was often: “I agree with you, but I can’t say that in public because I don’t want to get canceled.” If we couldn’t have the courage to govern ourselves, how could we expect the public to respect the principles of shared governance? Again, we’re now finding out the hard way the cost of these shortcomings.

When I became a professor, I promised myself that I would do things differently. I would “live not by lies.” I would treat my students of all backgrounds as full human beings, not symbolic avatars for their groups, or worse, totems for my or someone else’s politics. I would prioritize my integrity over professional incentives. I would trust that I had the skills to make a living regardless of any short-term professional consequences.

My refusal to self-censor has made me a better researcher and a better steward of my responsibilities as an academic.

Following these ideals meant not only challenging some progressive orthodoxies, but also not adopting the right’s reactionary mirror-images. I have publicly called balls and strikes on both sides of the political spectrum, and I will continue to do so.

This approach has ended up being more professionally rewarding than I had initially hoped. It has led me to some of the most impactful research projects of my career. It has led me to rewarding professional relationships, including with people who have made me smarter by challenging my thinking in ways I wouldn’t have been exposed to otherwise.

I have taken occasional public barbs from both sides of the political spectrum, but far more often I have been treated with respect. Overall, I’d say that my refusal to self-censor has made me a better researcher and a better steward of my responsibilities as an academic.

It has also been personally fulfilling. I don’t enjoy conflict, but I hate compromising my principles or ceding my integrity to bullies even more. The experience of taking barbs has made each one sting less over time. Being open about my principles has led me to new colleagues who share these principles. It has cost me a couple of friendships—which in hindsight I don’t miss—and it has gained me many more.

Tenure-track professors in the United States might have the greatest free speech rights in world history, and we have a moral and professional responsibility to use them.