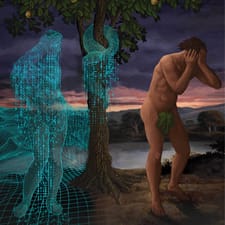

Adam’s First Eve

The first man’s first night on Earth holds valuable lessons for us

By Philip Getz & Daniel Levner

Illustration by Bob Venables (used with permission).

The sages of the Talmud once speculated about what it must have been like for Adam, the first human, to experience evening for the first time. They imagine Adam being filled not with marvel at the brilliant colors of his first sunset but with terror at the end of the only day he had ever known. “Woe is me, as because I sinned, the world is becoming dark around me, and the world will return to the primordial state of chaos and disorder. And this is the death that was sentenced upon me from Heaven.”

In this telling, Adam makes two immediate inferences from seeing the sky darken: First, that it signals the end of existence altogether, and second, that it is his fault. The sages’ version of the story continues with Adam spending all night fasting and crying, and his partner, Eve, crying opposite him. When dawn arrives and he realizes that the darkness has been temporary, he concludes, “This is the order of the world.”

If Adam’s fears seem extreme, they are also understandable. How else might someone thrown into the world ignorant of its workings react to the disappearance of light? How would the first man not fear for his survival upon seeing the world quickly become unrecognizable? How could he not wonder what role he might have played in the change? And what does this story teach us today about our own fears?

If there is some cautionary insight in this story, it is that it highlights two tendencies in human psychology: egocentrism and pessimism. The first, egocentrism, is most often observed in children from about two to seven years of age. Famed child psychologist Jean Piaget identified egocentrism as part of the preoperational stage of human development, during which children first begin to think abstractly, count on their fingers, and make up games and stories.

And because scientific knowledge is a product of the human mind, it is itself informed by the deeply human tendency toward pessimism.

These are all attempts by children to understand their place in the world, and their limited experience with others sets them up to see themselves at the center of that world. The logical conclusion of this can often be self-blame for occurrences beyond their control. Hence Adam’s belief that the physical workings of the universe are the result of his behavior rather than the other way around.

While delusions of egocentrism or solipsism can sometimes endure pathologically into adulthood, the human tendency toward pessimism almost always does, and this is for evolutionarily adaptive reasons: Always being on the lookout for potentially harmful outcomes can help a human being survive at any age. But what’s interesting about the human impulse toward pessimism, exhibited in the Talmud’s account of Adam, is that it often tends to focus on the monumental over the personal.

Studies show that even those who display optimism about their own personal lives are more likely to express pessimism when it comes to the future of their country or humanity as a whole. Psychologist Martin Seligman sees in this a link between optimism and a sense of control. As Max Roser and Hannah Ritchie of Our World in Data have put it, “Since we are in direct control of our own lives not the destiny of the nation, we feel more optimistic about ourselves.”

For the proverbial Adam, of course, there was no distinction between the two, and so his egocentrism and pessimism blended together to prompt him to think that the fall of the sun from the sky was inextricable from his own fall.

The emerging universe of artificial intelligence has given scientists, broadly defined, a sense of imminent darkness. It is as though the powers of this intelligence are so great we humans can hardly imagine inhabiting a world alongside it.

The sages’ story of Adam can be taken as an early allegory of empirical, even scientific, reasoning, and the potential blind spots of induction. Man’s inductive powers are only as powerful as the extent of his knowledge and the parameters of his perception. On the first evening, Adam, more keenly aware of his sin than of any other earthly fact, interpreted everything in this light, beginning with the absence of light.

And because scientific knowledge is a product of the human mind, it is itself informed by the deeply human tendency toward pessimism. Take for example the heat death theory of the universe first popularized by Lord Kelvin (William Thomson) in 1852. Kelvin’s theory, based on the Second Law of Thermodynamics, posits that the universe is indeed ultimately headed toward a final evening, a proverbial setting of its sun when it exhausts the energy to evolve further. The theory, which is widely regarded as the most plausible scenario for the universe’s demise, posits a time of maximum entropy somewhere between 1 trillion and a googol years from now, in which stars will no longer form and those that exist will burn out leaving existential darkness in their place.

The similarity (albeit on a different timescale) of Lord Kelvin’s theory with Adam’s nightmare scenario is amusingly uncanny, the difference of course being that neither Kelvin nor any other proponents of the theory seem to think humans have any control over what happens to the universe as a whole. But what we may have control over is what happens to our species, and there, too, the doomsday scenarios loom large in the human imagination.

The emerging universe of artificial intelligence has given scientists, broadly defined, a sense of imminent darkness. It is as though the powers of this intelligence are so great we humans can hardly imagine inhabiting a world alongside it. Having determined the course of many species that existed before us, we wonder whether we can survive the coming of a species of intelligence greater than our own.

We would do well to heed the words of Phish:

Approach the night with caution / It's the best that you can do / Move quickly through the darkness / 'Til the daylight is renewed / Approach the night with caution / You will know it's for the best / Once tomorrow's morning quells the thumping in your chest

The question is whether this eve of technological revolution will be more similar to the previous ones we’ve lived through until the next dawn, or fundamentally different, leading to an end to all sunrises. In their recently published If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies: Why Superhuman AI Would Kill Us All, computer scientists Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares make the case for the apocalyptic latter.

“Nature permits disruption. Nature permits calamity,” they remind us. “Nature permits the world to never be the same again.” Just ask the dinosaurs.

The fact is that this evening is fundamentally different from the one that so frightened Adam. Whereas Adam’s belief that his actions had brought about the evening turned out to be an egocentric delusion, we humans may have actually brought ourselves to the edge of light and darkness.

We are, as physicist David Deutsch has brilliantly explained, beings that create knowledge rather than simply perceive it. As philosopher Karl Popper put it, what distinguishes us from other species and the brutishness of the evolutionary process is that "we can let our theories die in our stead." But what if a new species of superintelligence grows out of our theories? Will the theory (or in this case, the species) die in our stead or not?

When Adam and Eve ate from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Bad it was because Eve had seen it “was desirable as a source of wisdom.” It is the perennial human temptation, to want to know more, and in particular to want to know more about what is good and what is bad. But like the first couple, whose “eyes were opened,” what we ultimately learn will, more than anything, be about the limits of our perception. And we too may come to see that we are naked.