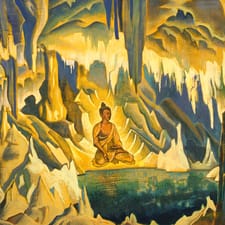

"Buddha the Winner" by Nicholas Roerich, 1925. WikiArt, Public Domain.

The spark for using socioeconomic class to teach Religious Studies came to me about six years ago. I had joined a small-group conversation of my students on the day’s topic of Liberation Theology. Discussion was heating up between one student, who insisted that prejudice against “visible minorities” represents the key social problem of our times, and another, who insisted that the concentration of power in the hands of “global elites” amounts to a bigger problem.

Looking to move their ideas forward, I asked whether they might bridge their disagreement by talking about power and oppression – usually thought of as issues of “class.” The first student insisted that this was exactly their point, but it had nothing to do with the other student’s view. The second dismissed any talk of oppression as communist. Both were blind to the potential for common ground.

Despite not succeeding in getting those two students to use “class” to think about religion, I have spent a lot of time since thinking about how to frame that idea in more accessible and less polarized terms – starting with the distinction between haves and have-nots. I’ve also thought a great deal about how discussions of class can be useful in some of my Religious Studies courses.

For those unfamiliar with Religious Studies, the discipline seeks to understand religions through the lenses of the humanities and social sciences. Of course, not every academic in the field approaches material the same way. For my part, I make an important qualification in the first session of every class I teach: Perhaps the most important questions we can ask from within a religion are “What does God expect of me?” or “How should I walk the path of my tradition?” But, if we accept the task of comparing all religions on something like an even playing field, we are limited to exploring religions as public, social forces in the world.

Even with that opening caveat, it isn’t easy to talk to undergraduate students about “class.” Many view socioeconomic class simply as a narrow form of indelible group membership, yet another box to be checked off. Students are used to seeing themselves in terms of different registers of identity: race, gender, ethnicity, sexuality, disability, nationality, language, neurodiversity, political beliefs, lifestyle choices – and sometimes religion. So, it makes perfect sense that they would read class, too, just in terms of identity politics.

If we ask how people use religion in struggles for more access to resources and opportunities, students can begin to understand both class and religion as they are experienced in societies around the world.

When students do encounter more sophisticated concepts of “class” – typically in humanities and social-science electives – the ideas often come in a confusing theoretical package. Like many of my colleagues, I could take the scholarly path and try to explain to my students concepts of false consciousness, commodity fetishism, surplus-value extraction, hegemonic discourses, and ideological state apparatuses. I could explore how class and religion intersect in Bourdieu’s view that “theodicies are always sociodicies” (as I have done before). Or I could think like a teacher and meet my pupils where they are.

After much thought and a few false starts, I now work with students to move away from thinking of religion as focused on a perfect world, whether beyond this one or in our hearts. Looking at religions as we do class – that is, in terms of political forces – helps students think about social hierarchy. If we ask how people use religion in struggles for more access to resources and opportunities, students can begin to understand both class and religion as they are experienced in societies around the world.

As an example, in my End of the World class in Religious Studies, in the section on East Asia, we discuss White Lotus groups. For well over a thousand years in China and more recently Southeast Asia, millennarian movements of this type combined social, economic, and political critiques of existing institutions and authorities with supernatural expectations for a coming utopian age. As I teach my students, if European Marxism is an echo of Judeo-Christian apocalypticism, then Maoism is an echo of White Lotus millennarianism.

Class comes into the picture here as we discuss a point made by U.K. scholar Seb Rumsby who observes that, in south-east Asian cultures, ethnicity – formerly seen as fluid – has become “a fixed, primary and primordial identity.” This development reflects European social Darwinism and was reified by communist governments in China and Vietnam. Millennarian social unrest had previously spread across ethnic and national boundaries, in part because distinct cultural groups saw themselves as sharing a subaltern socioeconomic position. But supernatural utopianism was siloed and contained as the reification of ethnic identity firewalled various sites of potential social unrest. The growing contrast between ethnic groups undermined previous socioeconomic solidarity. As I frame the point for students, where class once united, identity now divides.

Another effective example – discussed by scholars of religion like Russell McCutcheon – is the famous self-immolation of Vietnamese Buddhist monk Thích Quảng Đức. In June, 1963, Quảng Đức burned himself to death in a busy intersection in Saigon in an act of protest against the persecution of Buddhists. In my course, we begin by asking, “How was this a religious event?” But the idea that “Buddhist” was an identity worth dying for in such a painful way raises more questions than it answers. The stereotype that Buddhism is a religion of peace gets us nowhere.

The conversation moves forward when students do some research and find that the ruling elites in Vietnam at the time were Catholics, who tended to distribute power and opportunities among themselves. But a comparison of Catholic and Buddhist beliefs and practices also sheds no real light on the matter.

We then reflect on the words that have been popping up in our discussion. Why is it that words like “persecution,” “power,” and “oppression” seem more relevant here than “God,” “dharma,” “salvation” or “nirvana”? Then we read a few pages by Matthew Day, who explains:

- …the Catholic-Buddhist boundary in post-colonial Vietnam was energized by the antagonisms between an urban, expropriating elite and a rural, expropriated peasantry. Miss that and you’ve missed almost everything…. The slipup is … asking whether there is something uniquely “Buddhist” or “religious” about setting oneself on fire. … The most obvious questions, it turns out, are often the least revealing.

We split religions away from social and economic realities when we treat them as sets of ideas, symbols, and rituals about divine beings, afterlife salvation, and transcending this world, and when we teach religious history by focusing on ancient origins, sacred institutions, and diverging theological systems. Understanding class helps us fully understand religious life as an actual lived experience.

It isn’t easy to talk to undergraduate students about “class.” Many view socioeconomic class simply as a narrow form of indelible group membership, yet another box to be checked off.

Obviously, most religious studies scholars teach and write about real-world issues: religion and society, politics, violence, gender, sexuality, economics, and popular culture. But the “religion and” frame does not help my students understand these topics if it presents the religion part as uniquely spiritual, pure, and other-worldly, if it treats religion as ultimately transcending these other issues, even as it bridges to them.

We address this more explicitly in my course in a session where students research and present on religion as a mode of politics, choosing from a menu of topics like Engaged Buddhism, the U.S. Civil Rights Movement, Gandhian Satyagraha, and Nigerian Bishop Matthew Hassan Kukah’s critique of the “weaponization of religious identity.” These examples all show religions engaged in struggles between those with great power and those with less.

Ultimately, we arrive at a view of class – defined in general terms as social stratification according to material conditions and access to opportunities – by looking at how particular religions work in the world, not at how religion in general stands beyond it. If I succeed, students come to see that religions are not above the world but in its trenches. Their core ideas, values, and rituals are a particularly effective set of tools for both propping up and challenging disparities of power and opportunity. They are also effective pedagogical tools for recognizing and discussing disparities of power and opportunity.

Classroom discussions become more energetic when students and I approach religions as sites of shared political and economic – not only prophetic, scriptural, or soteriological – struggle. Some of that energy comes from recognizing that religion is also like politics in another way: there is no way to muddle through the contradictions and tensions that we face without getting our hands at least a little dirty. Purity and transcendence are myths – as active and ideologically double-edged as all myths are. There is a lesson here, too, for political views across the spectrum: the mutual demonization of polarized discourses are also problematically transcendent in their self-perceived ideological purity.

For various reasons – not hard to imagine – some students thrill at this trajectory of discussion while others do not. That divide sharpens and leads to further productive discussion when we bring it home to identity politics. Recognition, respect, and support for different racial, ethnic, gendered, sexual, disabled, and other identities is important and valuable, but it brings risks. Thinkers like Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt, Mark Lilla, Francis Fukuyama, Charles Murray, and John McWhorter suggest that identity politics fosters social division and undermines shared discourse.

In the end, can the relation between “religion” and “class” help students approach topics like social solidarity, tradition, and communities of shared values? The answer is “no” if students see religion and class as two more banners of siloed identity and difference.

But it is a qualified “yes” if we refuse to insulate religion from the world by wrapping it in a shroud of holiness, sacrality, and purity. If the essence of true, pure, orthodox religion is its other-worldly nature, then its social, political, and economic effects are pre-defined as secondary.

Over-emphasis on transcendence in Religious Studies blinds us to the real-world work of religion and, so, to its relationship with class. And, if any ideological stance – whether revolutionary socialism, identity politics, nationalism, or libertarian meritocracy – adopts a rhetoric of purity in order to reject competing views as less than morally immaculate, then it, too, is blinded by transcendence, and in need of more “class.”