Endangered Specimens, Unaccountable Objects

If anatomical collections are precious, then the public deserves to hear the reasons why.

By Michael Sappol

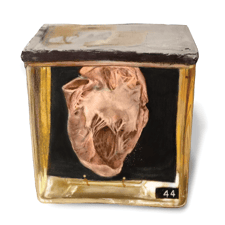

“Heart” by Pascale Pollier, artem-medicalis (used with permission).

Once upon a time, philosophers held up Anatomy as a paragon of Enlightenment science. The anatomist, they proclaimed, cast light into the dark interior of the human body. Practitioners of the discipline dissected the body into parts, drew boundaries, analyzed structures and functions, collected specimens, and made authoritative illustrated texts. These became prompts for critical reappraisal, further research, new texts, resulting in newer (better) knowledge.

But anatomy was also a dark science. Anatomists made knowledge from dead bodies illicitly obtained in the dead of night. Rituals of bodysnatching and dissection inducted students into the fraternity of professional medicine. The anatomical museum stood as a haunted house. And anatomical skeletons, skulls, and specimens served as emblems of human mortality, feature players in the danse macabre of medical student culture and the popular imagination.

I am a cultural historian of anatomy. And I study and love anatomical collections — though none are intact. A lot has been lost in the wreckage of war. (The Blitz destroyed two-thirds of London’s Hunterian Museum.) A lot has been lost through wear-and-tear and neglect. And a lot was discarded, as twentieth-century ideals of modernization and “scientific progress” pushed schools and hospitals to junk their shopworn, no longer state-of-the-art specimens and models.

Now comes a new threat, a moral panic. Critics are insisting that “human remains” — a misplaced blanket term for human-derived biomaterials — have no place in museums. Mostly they target ethnographic museums and skull collections which hold the skeletal remains and artifacts of indigenous and colonized peoples.

But historical anatomical collections are also getting caught in the net. Their objects were obtained without consent at a time when medical privacy and patient confidentiality weren’t respected. Ethical protocols for things like that didn’t exist then.

Philadelphia’s Mütter Museum – a jewel of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century anatomy – has just emerged from a two-year internal battle over the collections. Musée Dupuytren in Paris is closed. So is Padua’s Museo Morgagni. (Temporarily, let’s hope.) Other museums have removed specimens from view, restricted access, and re-evaluated policy.

Museum directors and curators are walking on eggshells. And, while all this is happening, laws that regulate medical research and records — enacted by officials who have no particular knowledge of medical history and scholarship — are also messing with the collections.

The burden is heavy, and curators and museum directors — who mostly love their collections — are crumpling under the weight.

Paradoxically, the roots of the present threat lie in an earlier movement to democratize medicine: the desire to open up has led to the closing down. In the latter decades of the twentieth century, many “legacy” collections, previously restricted to medical professionals, were refurbished and opened up to the public. Visitors came in droves to look at specimens that aren’t easy to look at. But now comes “the bioethical turn” and increasing discomfort with “insensitive” interpretations, provocative displays, and voyeurism.

The burden is heavy, and curators and museum directors — who mostly love their collections — are crumpling under the weight. The critics want to hold Anatomy to account. Yet museum curators and directors are mostly inaudible, reluctant to join the fray.

So, this essay is an attempt to speak up on behalf of the collections and objects. If anatomical collections are precious, the public deserves to know reasons why — why scholars and everyday people should get to see and study the specimens. Not just for purposes of medical research and lessons on the workings of the human body, but on historical, phenomenological, and aesthetic grounds. And for pleasure.

The objects of our legacy anatomical museums are artifacts and not just “human remains” or “medical specimens.” The medium is human flesh and bone. But also glass, wax, wood, preservative fluids and other materials. And some specimens are masterpieces of skilled dissection, artisanal craft, and technical ingenuity — as much a part of Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment culture as brilliant works of painting, metallurgy, and architecture — and just as worthy of preservation, display and scholarly examination.

You need to see them “in the flesh” to get what they are. So here’s Craniopago, the preserved head of an unviable conjoined twin. Or rather, here’s medical illustrator Pascale Pollier’s take — since, as I’ll explain in a bit, I was refused permission to use photographs.

What kind of object is it? Human biomaterial. A once-living thing which underwent sequential growth in the womb of a mother. She had, perhaps, a difficult pregnancy.

But Craniopago is also a scientific object, collected by a doctor who detached the head from the body, placed it in a glass pot with preservative fluid, and labeled it according to a taxonomic system for different types of conjoined twins. (“Craniopago” designates head fusion.) It was then transformed into a specimen among specimens, put on a shelf in the Museo Morgagni di Anatomia at the University of Padua for medical study and contemplation.

Today, it’s a historical object. And more than that. It has aesthetic and phenomenological effects, an aura. Asleep now in its slightly yellowed preservative fluid, quiescent in its luminous glass container. Beautiful, like a flawless sculpture in white Carrara marble. A compounded singularity. A folly of Nature. A silent rebuke to possessive individualism. Unaccountable.

It exists in a vitalist limbo, adjacent but not identical to personhood. Because some anatomical objects pull on us, even if they aren’t people. Like a cloud covering the sun, they somehow cause us to feel both presence and loss.

Some anatomical objects pull on us, even if they aren’t people. Like a cloud covering the sun, they somehow cause us to feel both presence and loss.

In 2019, I visited Museo Morgagni and its brilliant collection. Last year, I respectfully requested permission to photograph Craniopago and other specimens, for research and eventual publication.

That request was denied. A curt formal reply from University of Padua professor Monica Salvadori refused permission because the issues I wanted to write about (uncertain histories, conflicting ethical claims, anatomical aesthetics) were “inappropriate.” Referring to a Mussolini-era decree on privacy, Salvadori demanded that I “cease and desist” from using the name of Museo Morgagni and the University of Padua.

The tone of the refusal shocked me, and a group of scholars rallied around with a public letter protesting the decision as a violation of the principles of academic freedom and public access. Later, in a newspaper interview, Salvadori doubled down on the decision, explaining that the museum’s governing ethical principle is to “equate…the organ with the person and his universal rights to privacy.”

But think about that leap from body-part to person. A fetus in a jar. A heart. A slice of tissue on a slide…. All transformed into persons who, after more than a century, somehow still require privacy protections? In most cases, we don’t know the names of the people whose bodies were requisitioned to supply tissues, fetuses, and body-parts for medical research. But even if we did, what harm would it now do to allow scholars and the public to see those things in a museum setting?

Salvadori went on to denounce the “spectacularization” and “theatricalization of human remains,” which “in America is a very developed activity.” That dubious assertion painted me as an exploitative showman and not a credentialed historian with a track record of peer-reviewed books and articles. It also overlooked the awkward fact that the Museo had, only some years earlier, authorized publication of a book of arguably theatrical photographs of specimens in a volume bearing the imprint of Bizzarro Bazar. (Images from the book can be downloaded on the Web; [1])

Salvadori’s argument channeled current bioethical discourse with its themes of dignity and respect for patients, research subjects, and human remains [2]. These themes are, of course, vitally important. But too often nowadays they take on the prosecutorial tenor of a culture war — a species of bioethical maximalism — mostly emanating from the feminist, decolonizing Left. The target is the Museum, capital M, which seems mighty, a direct perpetuator of the colonizing imperialist past.

But anatomical and pathological museums aren’t mighty. Museo Morgagni isn’t the British Museum or the Louvre. Instead, like most historical anatomical collections, it’s fragile and underfunded, administratively and institutionally insecure. By the sufferance of university management, it occupies a basement in the medical school.

The critics think they’re punching up, but they’re really punching down. I’ll here rely on cultural critic Namwali Serpell to say it: this kind of activism is “divorced from real politics: the legal battles, power structures, and acts of violence we still face” [3]. Quibbles over the display of old anatomical specimens amount to fiddling while Earth burns.

And the quibbles don’t help us to apply ethical principles in a way that respects the history, with all its nuances and contradictions, and preserves remnant historical artifacts for present-day scholars and a diverse and diasporic global public. The concept of universal human rights is a precious cultural and ethical achievement. But what if the universal rights to privacy and death with dignity clash with the universal rights to transparency and access, in a world in which transparency and access are key elements of a universal need to know our collective history, in order to understand the present?

But what if instead we live with the objects? Study or be appalled or take pleasure in them? Understand them as artifacts of our shared history.

Were we to adopt a maximalist position on the principles of universal human rights of dignity and respect for the dead and their anatomized parts, identity or historicity wouldn’t matter. An essentialist view would classify every anatomical specimen as a “sensitive object” and “ancestral remains.” Lacking evidence of informed consent to the donation and its uses, we would be obligated to take all specimens off display, claw back photographs, both printed and digital – paper archives, too. (No statute of limitations on personal privacy protection.) The collections would be thoroughly dissolved, the objects “returned” to biological descendants or provided some kind of “decent burial.”

But what if instead we live with the objects? Study or be appalled or take pleasure in them? Understand them as artifacts of our shared history.

The accumulation of knowledge we group under the rubric of Science and Progress comes only by way of a long list of original sins. If the anatomical museum is a crime scene, we ought to keep it intact for forensic analysis, historical research, interpretation and cogitation.

And keep archives and collections open. In copyright law, after a designated period of time, works are released into the public domain, a cultural commons. No rights-holders or paywalls. Once-copyrighted objects are transformed into a collective inheritance, free and accessible to everyone.

That’s how we should treat historical anatomical objects. But with a carve-out. Plundering, assault, robbery, murder, and enslavement really did happen. So, understandably, descendants of people who suffered from calamitous oppression — who suffer still from the legacy of that oppression — want their material back. When repatriation is reasonable and feasible, objects, whether biomaterial or not, should be returned.

And yet. With all the disruptions of historical change, there will always be vexed questions about who should rightfully receive the goods, and what should be done with photographs and other derivatives. Given the great shuffling of things, we can’t put everything back in place. And it’s often not wise or just to do so.

Because, over time, there’s also been a great shuffling of persons. Descendants of indigenous, colonized, and persecuted peoples now live in the heart of Europe and all over the world. Our civilization is diasporic, global, hybridized. We are all, in varying degrees, colonized and decolonized. We all have anatomical bodies, an anatomical sense of self, which is a historical phenomena, something that developed in our now global civilization over the centuries. And, as the inheritors of that fragmented and morally ambiguous anatomical legacy, we’re burdened and blessed with its fragile unaccountable objects.

References:

- ^ 1. Ivan Cenzi, Carlo Vannini, Alberto Zanatta, Sua Maestà Anatomica [His Anatomical Majesty], trans. David Haughton (Modena: #logosedizioni, 2016)

- ^ 2. Antonello Caporale, “Cuori, fegati e milze: il ‘museo’ della morte che celebra la vita,” II Fatto Quotidiano (6 March 2024): 15; see also Michael Sappol, letter to editor, II Fatto Quotidiano (14 March 2024).

- ^ 3. Namwali Serpell, “ ‘Such womanly touches,’ ” New York Review of Books (2 Nov 2023): 45.