Helper, Partner, Scapegoat

Tenured faculty need to start to see “academic staff” as full-fledged colleagues

By Julie Rojewski

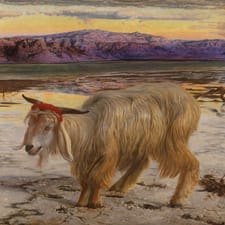

"The Scapegoat" by William Holman Hunt, 1854. Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons.

There is no doubt that in higher education, the administrative bureaucracy has expanded exponentially in the last few decades. University faculty and others have loudly lamented this expansion, blaming this ever-growing cadre of “administrators” for the rise of costs, the growth of intolerance in academic culture, and a decline in the focus on academics and scholarship.

While this administrative bureaucracy has certainly grown in the areas and departments you might expect, like accreditation, compliance and legal, it has also increased in core academic areas. Specifically, there has been a tremendous increase in “academic staff,” a broad term that often includes roles that are not entirely academic, not quite administrative, but something in between.

These quasi-academic, quasi-administrative employees play an increasingly visible role at universities and colleges, blurring the lines of what we think of as “faculty work,” such as teaching and advising students. For many faculty, the distinction is clear: Real faculty have tenure or are trying to earn it, while literally everyone else is not faculty. And yet this oversimplification belies what’s actually happening on campuses across the country.

Imagine a new college student, trying to find their way around campus during the first few weeks at a large university. They’ve probably already met with an academic adviser (who likely has a graduate degree) in order to select electives, discuss how courses might relate to a possible career goal, and map out a plan to graduate. Perhaps this student feels underprepared for the rigors of college work, and so they head over to an academic support center, where a different team of de facto educators works with them on developing new study skills.

Eventually our new student starts classes, which may well be taught by graduate students, adjuncts or academic staff. On many campuses, such people offer a student their first real exposure to the university classroom, giving them an introduction to important disciplines and teaching them how to effectively write and critically interpret a text.

The interests of universities and their students are best served when all members of the campus community are encouraged and supported to engage in the life of an institution.

Indeed, during their first few semesters, students are more likely to encounter these “academic staff” than tenured faculty members, the most detached of whom brag about what they do to avoid teaching intro classes and try their darndest to work primarily from home to avoid parking woes, in-person encounters with students, or requests to sit on academic committees.

At the same time, HxA members and other academics routinely lament students’ unwillingness to engage in difficult conversations, to push for heterodox ideas, to be bold and outspoken in the pursuit of truth. But where, and from whom, should students be expected to learn such intellectual habits?

Should the adjuncts and other non-tenure-track faculty who are teaching so many of the intro courses risk losing their jobs by being too provocative during a discussion section for first-year students? What about academic staff who are often seen and treated as “second-class faculty” because, surely, they are not “good enough” to land a tenure-track role? Are those the people who should be inspiring students to think big, bold thoughts and to be daring enough to share them? Are those the people whose job it is to advise and mentor students?

When we talk about the growth of the academic bureaucracy, we are talking, in part, about these people. When we talk about the erosion of faculty influence on decision-making at an institution, we are also talking about these people, in part because they have taken on roles that emerged after tenured faculty members decided they no longer had the time to do things like teach intro courses or participate in curriculum redesign.

Academic Staff as Eve

The term “academic staff” can mean many things, but it generally refers to full-time roles that tackle some aspect of the traditional faculty triad, be it research, teaching or administrative service. Such roles are usually held by people with advanced degrees. Sample nomenclature for the job includes “academic specialists,” “teaching faculty,” “faculty associate” or other, similarly vague terms that use “faculty words” for non-tenure-track, faculty-type jobs.

Meanwhile, despite these academic staff roles becoming more and more commonplace, the people in them are nevertheless often treated as inferior to “real” faculty. And just as Eve was often seen as being created to make life easier and better for Adam, so too are many academic staff viewed as supporting the “real faculty,” by freeing them up to pursue their academic interests rather than teaching and advising students.

And if you’ll allow me another Eve analogy, many of the people who do these jobs are women. Women comprise nearly 49% of all types of faculty, which makes sense since women earned 48.6% of the doctorates awarded in 2024. But when you break down the numbers on women faculty, only 25% or just over half of the 49%, are in tenured or tenure-track positions, while the remainder (23.5%) are in “academic staff” roles.

By contrast, 31% of men are in tenure-track faculty slots, and only 19% are in academic staff roles. So women are much more likely than men to find themselves working off the tenure-track and in faculty-adjacent roles that increasingly lack the job protections and stability afforded to colleagues on a narrowing tenure track.

What explains the rapid expansion of academic staff? Critics name several factors, including the need for more-specialized bodies of knowledge to run modern universities, the need for maximum flexibility in staffing to respond to fluctuating enrollment numbers, an increasingly complex research environment that requires narrow, specialized skill sets for support, and the overproduction of Ph.Ds. At the same time, tenured faculty members don’t have time to do many of these tasks, or they aren’t incentivized or rewarded to do them, and as is often the case, they simply don’t want to do them.

To look at it another way, someone needs to be on campus to meet with students, advise them, attend meetings where institutional decisions are made, ensure that the curriculum evolves to meet accreditation standards, and engage in other critical conversations with academic implications. And if tenured faculty members aren’t available or willing to do such work, academic staff will.

Rather than retreating from the administrative life of the university, tenured faculty should use their influence and tenure protections to advocate for expanded inclusion of more voices.

Scapegoat or Partner?

Eve’s inability to resist the apple, her curiosity and daring to acquire knowledge that might be equal to Adam’s on paper, her audacity to want to use her education to contribute important functions to the teaching of students and support for the university are all swept aside when she plays another critical role: scapegoat for all that is wrong in the modern university. According to critical faculty voices in HxA and beyond, it’s always “the administration” that is doing harm to the important intellectual work of a university.

What’s more, to truly expand values of open inquiry and constructive disagreement on college campuses, values that the Heterodox Academy was founded to promote, we must work collectively to ensure that all members of a campus community have the freedom and support to truly be themselves and to model viewpoint diversity. We cannot reserve open inquiry only for faculty who have the formal protection of tenure and leave “the others” to fend for themselves.

This is especially important because, as already noted, academic staff may be teaching many of the courses taken by first- and second-year students. And so if we want advanced undergraduates and disciplinary majors to show up in a seminar classroom with the ability to think critically, to tolerate intellectual discomfort, and to listen to those with whom they disagree with both charity and with humility, then they need to be taught these intellectual habits at the outset of their academic experience, not halfway through it.

The interests of universities and their students are best served when all members of the campus community are encouraged and supported to engage in the life of an institution and shape the decisions that determine its future. Instead of avoiding service opportunities, faculty can ensure their perspective is heard by showing up for the meetings and representing that perspective. Instead of shirking the important work of helping incoming students, tenured faculty can take a greater role in teaching intro and survey courses.

And rather than retreating from the administrative life of the university, tenured faculty should use their influence and tenure protections to advocate for expanded inclusion of more voices, embracing the most expansive definition of “faculty” to affirm faculty power and create the kind of campus cultures we claim to want.

There are any number of threats confronting institutions of higher education at present. The snakes are growing in number and getting stronger, and the Adams and Eves of the academy need to unite to fight them and preserve the intellectual integrity of the ivory tower and its garden of ideas. But this can only happen when faculty members begin seeing and treating academic staff as important and equal partners.