Illustration by Janelle Delia using “The Double Secret” by Rene Magritte.

Enlightenment era scholars, like many classical scholars before them, believed that human cognition was fundamentally oriented towards truth, objectivity, and logic. Deviations from this ideal were held to be caused by forces external to our minds: our physical appetites, social corruption, or malevolent supernatural entities.

Contemporary scientific consensus now holds that thinking is not something that occurs exclusively within our individual minds; it occurs primarily in conjunction with others, and in dialogue with our physical and social surroundings. At a fundamental level, we think with and through other people and our environments in much the same way as we think with and through our physical bodies.

Working and thinking together in this way, we’ve developed means of traveling into space. We can split atoms. We can communicate instantaneously across continents. We can prevent people from contracting diseases like leprosy and polio that have long ravaged humankind. Collectively we are capable of remarkable intellectual feats.

However, at the individual level, our ability to understand the world is inevitably constrained in some highly consequential ways. Consider the process of perception. It’s simply impossible to attend to all the information that is available to us at any given time. And of the things we do pay attention to, we can’t remember everything we notice indefinitely.

Instead, we have to make decisions about what to focus on, organize observed details into a relatively stable and coherent picture, and make inferences about what it all means. This process typically unfolds instantaneously and largely unconsciously. And for good reason: in the real world, we can’t sit and ruminate indefinitely. Fortunately, under most conditions, our intuitive cognitive systems are reliable, quick and highly efficient.

Importantly, the decisions we make about what to focus on (or not), what we remember and how we remember it (or don’t), and how to interpret ambiguous signals—these choices are not made in a random or disinterested way. Our brains are not designed to produce an “objective” and “true” picture of the world. Instead, reflecting their social origins, our cognitive capacities are oriented towards perceiving, interpreting and describing reality in ways that enhance our personal fitness and further our goals.

Scholars are not immune to these temptations. In many respects, we may be more susceptible.

For example, we pay attention to, easily recall, and feel positive emotions towards things we deem interesting or useful. We dismiss, downplay, dump, and have negative emotional reactions to information that is threatening to our objectives or our self-image, or that conflicts with our expectations or pre-existing beliefs. Things that don’t seem particularly significant in either direction, we largely ignore, even though sometimes these neglected details prove to be quite important.

Collectively, these systematic distortions are known as “biases.” And, critically, it isn’t just our perception that’s biased. The causal stories we tell are, too. So are our choices of alliances. Our natural impulses are to sort into groups with people who share our values, politics, and other identity commitments, to publicly bring ourselves and push others into conformity with the group, and try to suppress, exclude or dominate others with incompatible goals and perspectives. Our default inclination is to perceive, interpret, and describe the world in ways that flatter our self-image, advance our interests and reinforce our existing worldviews—while explaining others’ deviance from our preferred positions through appeals to deficits and pathologies.

Scholars are not immune to these temptations. In many respects, we may be more susceptible.

Article Image by Janelle Delia manipulated using “The Double Secret” by Rene Magritte

For instance, people who are highly educated, intelligent, or rhetorically skilled are significantly less likely than most others to revise their beliefs or adjust their behaviors when confronted with evidence or arguments that contradict their preferred narratives. Precisely in virtue of knowing more about the world or being better at arguing, scholars are better equipped to punch holes in data or narratives that undermine our priors, come up with excuses to “stick to our guns” irrespective of the facts, and interpret threatening information in a way that flatters our existing worldview. And we typically do just that.

Hence, rather than becoming more likely to converge on the same position, people tend to grow more politically polarized on contentious topics as their knowledge, numeracy, reflectiveness increases, or when they try to think in actively open-minded ways.

Highly educated people may be particularly prone to tribalism, virtue signaling and self-deception.

In a decades-long set of ambitious experiments and forecasting tournaments, psychologist Philip Tetlock has demonstrated that—as a result of their inclinations toward epistemic arrogance and ideological rigidity—experts are often worse than laymen at anticipating how events are likely to play out…especially with respect to their areas of expertise.

Contrary to our own self-perceptions (and self-descriptions), cognitively sophisticated, academically high-performing, highly educated people may be particularly prone to tribalism, virtue signaling and self-deception. We tend to be less tolerant of views that diverge from our own. We are also more prone to overreact to small shocks, challenges, or slights.

In short, the kinds of people most likely to become academics are more likely than most to be dogmatic ideologues or partisan conformists. Subject-matter expertise and cognitive sophistication doesn’t empower folks to overcome the general human tendencies towards bias and motivated reasoning. If anything, it can make it harder.

Here it should be emphasized that these cognitive tendencies are not necessarily pathological. In general, our biases and heuristics allow us to process and respond to extraordinary amounts of information quite quickly. We could scarcely function without these distortions. Ostensibly irrational levels of confidence, conviction, resilience and optimism often play an important role in perseverance and even success. Our biases and blindspots are, therefore, not just a product of our cognitive limitations; they empower us to accomplish things we otherwise may not. In Nietzschean terms, our cognitive distortions serve important life-enhancing functions.

That said, it is also an empirical reality that biases often do cause practical problems, especially with respect to knowledge production, and particularly when it comes to contentious social topics. Our socially-oriented cognition (seeking status, tribal victories, and the like) often supervenes even sincere attempts to pursue the truth wherever it leads.

Exacerbating this issue: the specific things we study—and how we choose to study them—are themselves often deeply informed by our fundamental commitments and life experiences. Scientists are not randomly assigned areas of study, after all. We gravitate towards the specific questions we investigate, and the specific methods and theories we use to investigate them, for all manner of personal and social reasons we may or may not be conscious of. And upon selecting topics of interest, personal commitments and beliefs shape how we approach research questions at a fundamental level.

To illustrate the scale of this issue: studies consistently find that one can present sets of researchers with the exact same data, to investigate the exact same question, and they’ll typically deliver highly divergent results. This is not just true for contentious social and political questions. The same realities have been observed in the life sciences, technical fields, and beyond. This is one of the main reasons studies often fail to replicate—not necessarily due to flaws in original study or the replication, but because each party made slightly different but consequential choices that led them to different conclusions.

Put simply: scientists cannot simply “follow the data” and arrive at “big-T” truths.

In fact, even the act of converting messy and complicated things and people “in the world” into abstract and austere data that can be easily communicated, transformed and operationalized—this is itself a highly contingent process, deeply informed by the assumptions, limitations, and desires of the data collector. And said data get subsequently analyzed and presented as a result of choices scholars make, driven by myriad “trans-scientific” factors. There is really no way to avoid this.

It’s possible to collectively check and transcend our own individual cognitive limitations and vices.

The good news is, we aren’t forced to contend with these problems by futility trying to pull ourselves up by our own bootstraps. Science is a team sport. And under the right circumstances, it’s possible to collectively check and transcend our own individual cognitive limitations and vices. In contexts where researchers approach questions with different sets of knowledge and experiences, different material and ideal interests, using different methods, and drawing on different theoretical frameworks and value systems, we can produce something together over time that approaches objective, reliable, comprehensive knowledge.

With this possibility in mind, many systems in science and education have been designed around institutionalized disconfirmation, adversarial collaboration, and consensus building. For instance, decisions about who to admit, hire and promote within departments are supposed to be made through diverse and rotating committees of scholars hashing out the merits of various candidates together. Decisions about what to publish are supposed to be made by multiple, (double) blinded peer reviewers, themselves selected and checked by editors. And so on.

However, these systems only work as intended when there is genuine diversity within a field across various dimensions. In its absence, the same systems, norms and institutions that are supposed to help us overcome our limitations and biases can instead exacerbate them. They can stifle dissent and innovation. They can lead to collective blind spots and misinformation cascades. In contexts like these, important details and possibilities can be right in front of scholars’ faces, but it can be almost impossible for anyone to “see” them.

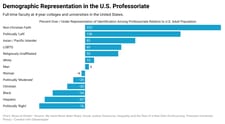

If we care about quality knowledge production, we must acknowledge that a major problem we face today is that the U.S. professoriate is drawn from a narrow and highly idiosyncratic slice of society along virtually all dimensions. Consider the skews in this chart:

Similar realities hold for most other institutions of knowledge and cultural production. Bias, the exclusion of outgroups, and the suppression of inconvenient findings are not new issues. Research on how these tendencies influence knowledge production goes back more than a century—as do organizational efforts to mitigate these challenges.

The problems we need to overcome are not novel products of “kids these days,” “wokeness,” or adjacent contemporary developments.

Because these tensions arise from fundamental aspects of our cognition, the resultant problems must be actively and perennially managed. Put another way, the problems we need to overcome are not novel products of “kids these days,” “wokeness,” or adjacent contemporary developments. They are persistent problems related to human nature. They will endure as long as modern science does because, in a deep sense, what we are trying to do as scientists is unnatural.

It is not natural, and in fact it’s often deeply unpleasant, to slow down judgment and think more carefully—taking care to avoid biases, oversights or errors. It’s not natural to work amicably with people across lines of profound difference, for example, making decisions about things like admissions, hiring and promotion purely on the basis of merit. It is not natural—and in fact, it is very difficult (although quite important)—to recognize and publicly acknowledge error, and then revise our attitudes, beliefs and actions in accordance with the best available evidence.

And in itself, awareness of these biases and limitations in itself doesn’t tend to change much because, in practice, people tend to think of themselves as exceptional. Most view themselves as smarter, less biased, and more authentic and moral than average. We tend to think that the forces that bind and blind everyone else do not govern our own attitudes and behaviors to the same extent. Other people (especially those we don’t identify with) are driven by self-interest, ideology, and so on. We are motivated by strong ethical standards, including a principled commitment to the truth.

Sociologist Andrew Abbot referred to this as “knowledge alienation”: declining to apply information we have about the world to ourselves and the institutions and groups we identify with.

Indeed, even when we intellectually recognize that we are susceptible to bias and error, it’s hard for us to actually feel that way, especially in moments of contestation. This is because, with respect to many cognitive distortions, our brains seem designed to avoid recognizing our biases. We have “bias blind spots” that interfere with our ability to recognize when our cognition is going astray. And even when we actually recognize that we may be engaging in motivated reasoning, the social motivations undergirding that reasoning often help us justify our biases to ourselves and others.

As individual scholars, no matter how committed or well-intentioned, we cannot escape our social brains. To produce, we need to engage with people who don’t share our interests, priors, values, and experiences – which requires a commitment to folding a broader swath of society into the research enterprise and expanding many conversations beyond the Ivory Tower. We need institutions, norms and processes that help discipline our degrees of analytical freedom, and that help us evaluate the quality of work in consistent and fair-minded ways. We need investments and protections that help enable intellectual risk-taking, adventurousness, dissent and conflict – even when colleagues are inclined towards censorship, and even when this censorship is itself intended to serve prosocial ends (as is typically the case).

We can actively strive to integrate a wider range of perspectives and stakeholders into our institutions, our research, our teaching, and our learning. And we should, because the only way we will ever peaceably answer the perennial and the pressing questions of our day is if we leverage, rather than suppress, the diversity of our humanity.