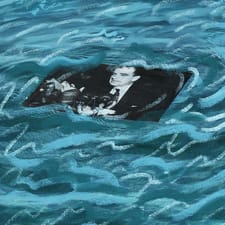

Just Below the Surface

Could censorship on campus ignite a resurgence in creativity?

By Matt Moreali

Photo Illustration by Janelle Delia (used with permission).

The explosion of creative expression following the end of McCarthyism is a popular example of the pressure cooker effect, which is when sustained oppressive forces paradoxically create a sudden counterreaction. While the 1950s did see innovations in art, entertainment and technology, some attribute the conformist pressures of that time to sparking an even greater boom in creative expression that followed in the 1960s.

Might we be on the eve of a similar creative explosion today? Certainly, there are parallels between what’s been happening on campuses in recent years and what occurred during the McCarthy era. If anything, censorship on campuses today may be even worse. For instance, a survey conducted in 2024 by the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) found that faculty members were actually much more likely to self-censor their writing than scholars reported during the 1950s. Specifically, 35% of contemporary scholars report toning down their writing versus 9% during the McCarthy era.

FIRE is not alone in drawing this connection, as anecdotes of campus shutdowns and zealous bias reporting over the past decade have invoked comparisons to the Red Scare. Some critics have also compared the recent fiscal and legal attacks on universities by the Trump administration to government coercion under McCarthyism.

So, in our current moment, higher education faces pressure from both internal and external forms of censorship. Whether this dynamic ultimately leads to a new blossoming of creative expression depends on how university administrations and faculty respond.

While censorship and self-censorship typically undermine creativity, they may also paradoxically inspire it, at least in some contexts. Of course, the ideal environment for creative thinking remains one in which ideas flow freely, without fear of censure or retribution. Indeed, while the First Amendment explicitly protects the right to expression, it also implicitly guarantees the listener’s right to obtain information, enabling the free exchange of ideas.

But while having fewer ideas in circulation results in less knowledge being available to inspire originality, catalyze discourse and pursue a deeper understanding of the world, censored ideas can still be shared subversively through networks that skirt the boundaries of suppression. For instance, poets facing repression in the 1950s founded new journals and experimented with literary styles in conflict with the constraints of McCarthyism.

Similarly, a contingent of contemporary scholars has reacted, both openly and under the radar, against recent censorship in higher education. The emergence of ideas, communities and publications from scholars affiliated with organizations such as FIRE and Heterodox Academy is arguably the result of perceived campus repression. This exemplifies how novel views and approaches may develop despite, or maybe even because of, restrictions on the expression of certain ideas.

While censorship and self-censorship typically undermine creativity, they may also paradoxically inspire it.

Furthermore, censorship’s impact on creativity can often depend on the nature of the repression at issue. For instance, informal repression may induce greater self-censorship because standards are broader and not limited by procedural safeguards. Such vague and undefinable forms of censorship stultify the creative process and encourage a tendency to avoid crossing an amorphous line of acceptability. By contrast, the delineated boundaries characteristic of formal censorship may encourage daring speakers to craft their expression up to those limits as an exercise in creativity.

Censorship’s impact on creativity in higher education may also depend on whether its source is internal or external. For instance, some argue that internal assaults on free speech during recent decades have been worse than were the external threats from the government during the McCarthy era. Under this view, attacks from McCarthy unified the academy, coinciding with a period of cultural flowering, while internal attacks during the 1990s and beyond divided the academy and to this day remain disastrous for discourse. Since people tend to have a heightened reaction to government censorship compared to other forms of repression, it may partially explain the cohesive resistance to McCarthyism as opposed to the disjointed infighting in response to censorship from the 1990s onward.

At the same time, the current external threats from the Trump administration could override the self-censorship we’ve seen in recent decades and encourage a communal resistance of the sort that opposed McCarthyism, leading to another pressure-cooker effect. Indeed, data from the FIRE report indicates contemporary scholars have more potential expression bottled up because the nature of the recent self-censorship has been more sustained and internalized. This phenomenon may also result in the release of creative expression uniquely representative of the current moment.

At the end of the day, of course, it’s hard to know what will happen. The dual nature of contemporary censorship may exert enough pressure to either ignite a creative renaissance or perpetuate the flattening of a demoralized professoriate. After years of trying to avoid offending the campus orthodoxy, combined with the prospect of layoffs from recent federal action, some might behave as if they have nothing, or everything, to lose.

Personally, neither extreme resonates with me, but I do feel a sense of urgency to express withheld ideas during this period of flux. If many other faculty members share this sentiment, albeit with greater contrarian and creative capacities than I, then current conditions could be ripe for a creative revival.