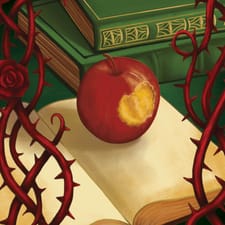

The Forbidden Fruit of Uncomfortable Ideas

Both people and institutions need to learn to embrace disagreement

By Barbara Oakley

Illustration by Janelle Delia (used with permission).

Eve wasn’t being especially rebellious when she reached for the apple—she was just acting like a human being, with all of the curiosity that has come to define us as a species. That same impulse, the irresistible need to know, has fueled virtually all human progress throughout history. Yet today, in some of our most “enlightened” institutions, even asking certain questions can feel like biting into forbidden fruit.

What if the real problem isn’t the questions themselves, but our fear of asking them? Specifically, what happens inside us when we hear something we’d rather not? And what does that visceral reaction mean for free speech at work, on campus and in our closest relationships?

That’s the territory we cover in Speak Freely, Think Critically—to our knowledge, the first large-scale online course on free speech grounded in neuroscience. The course is offered for free on Coursera, an online platform that now reaches nearly 200 million learners in over 200 countries. My fellow instructors and I don’t dwell on case law or the First Amendment. Instead, we explore why disagreement feels threatening—and what it takes, both individually and institutionally, to stay in the conversation. Our focus is on belief itself: how it forms, hardens and defends itself when challenged.

The course couldn’t come at a better time. In many of today’s classrooms and boardrooms, no one usually has to stop people from asking difficult questions. That’s because those questions simply aren’t asked. Often that silence is born of good intentions—a desire not to offend or to avoid conflict and preserve harmony. But when “safety” is defined as avoiding discomfort, curiosity itself becomes dangerous and people quickly lose their ability to think critically, while institutions lose their ability to self-correct.

People can instinctively weight their own community’s beliefs more heavily than outside views.

Neuroscience helps explain why. The brain’s fast, automatic systems turn repetition into habit—not only for motor skills, but for patterns of thought. When we hear often enough that someone is dangerous or evil, those grooves can lock in. Research by Jean Decety at the University of Chicago shows part of how this unfolds. Brain circuits that normally light up with empathy go quiet when people watch those branded as “them” in pain. That neural silence makes it easier to turn away. Greg Lukianoff, a leading free speech advocate, calls this a “rhetorical fortress”: Once a person or idea has been cast as beyond the pale, the fortress gate slams shut. No contrary idea gets through, not because it’s wrong, but because the speaker has already been cast as a monster.

I’ve seen that reaction firsthand. When we mentioned we were developing a course on free speech, some people’s faces froze—their expressions shifted as if a sudden chill had entered the room. I recognized that look because I’d felt it myself as a teenager working in a veterinary clinic. The first time I was asked to help in surgery, I froze and wanted to look away. But I had a job to do, and I couldn’t help if I flinched. By holding steady, I learned that what felt unbearable at first could become a threshold, not a wall.

The recent assassination of Charlie Kirk at Utah Valley University starkly illustrates how the rhetorical fortress can enable real violence. While Kirk’s death is first and foremost a human tragedy—leaving behind a widow and two young children—the response from some quarters revealed just how deeply the dehumanization has taken root. What many don’t realize is how their emotional responses have been orchestrated by thousands of subtle cues: the careful word choices, the selective framing, the images chosen, the stories amplified or buried. Like water carving a canyon drop by drop, these micro-messages accumulate until hatred—and the murder of a young man—feels not just justified but righteous.

Perhaps most telling is the contrast in how Kirk’s death has often been framed versus George Floyd's. Where Floyd's killing was condemned as an unacceptable tragedy worthy of “mostly peaceful” protests, Kirk's murder is often portrayed as somehow both deserved and divisive. Some educators even expressed glee, their empathy circuits apparently offline—not because they're naturally cruel, but because years of rhetorical conditioning had transformed a father and husband into a caricature unworthy of human feeling.

Listening to someone with an opposing perspective isn’t about conceding the point or winning the argument. It’s about keeping your mind flexible when every instinct says to shut down—or to strike back.

This is how the basal ganglia's habit-forming machinery gets weaponized. Each small bias reinforces the next until even witnessing a murder can feel like justice. When we allow any human being to be cast as irredeemably evil through this slow drip of dehumanization, we create the conditions where violence becomes not just thinkable, but inevitable.

Shared bonds can encourage group think. People can instinctively weight their own community’s beliefs more heavily than outside views. That unity can drive resilience, but it can also blind us to anything but ideas and information that affirm our views. During COVID-19, for example, governments tilted public discourse by making certain perspectives harder to find and others easier to dismiss.

The lesson is bipartisan: Gatekeepers rarely filter information in ways that inconvenience their own side. And our sense of truth is further warped by familiar mechanisms—social proof (believing something because others seem to), source amnesia (forgetting where we learned a claim so propaganda can be “remembered” as fact), and algorithmic curation (a TikTok “For You” page or a Facebook feed that learns your preferences). Together, these forces trap us in echo chambers we mistake for the real world.

Institutions, meanwhile, don’t just rely on silence. Leaders with narcissistic streaks treat criticism as an attack. Administrators, eager to protect, expand lists of topics that are off limits. Departments seeking cohesion quietly freeze out contrarians. No decree is needed; opportunities just vanish, invitations stop, and the dissenter runs into a wall.

In our course we don’t just examine the hows and whys of these problems, but also explore solutions. For instance, Community Notes on X (which allows people to fact-check each other’s posts) requires that people who typically disagree reach consensus before a note can appear—a small but powerful demonstration that cross-partisan agreement is possible within the right structure. Students in the course practice the same skill through Sway, an AI-facilitated platform that pairs them with differing viewpoints and guides them toward mutual understanding. The goal isn’t persuasion; it’s perception, improving your own thinking while truly grasping an opposing stance. That’s cognitive cross-training.

One surprise has been the audience for the course. We expected students and faculty at universities, and they’re there. But we’ve also heard from those in the business world who sense how the pursuit of “psychological safety” can slide into fear of disagreement, hurting their companies’ competitiveness. When the highest virtue is avoiding discomfort, the toughest questions go unasked—not because we don’t see the problem, but because we don’t want to be accused of insensitivity.

This understanding, to me, is the fruit Eve reached for: not just knowledge, but self-knowledge. Discomfort itself can be a signal of growth. Recent work by Cornell University’s Kaitlin Woolley and Ayelet Fishbach of the University of Chicago shows that when people are encouraged to actively seek discomfort—in improvisation classes, expressive writing, or even in opening themselves to opposing political views—they persist longer, take more risks and come away with a stronger sense of progress. Instead of treating unease as a stop sign, people can learn to see it as evidence that growth is happening.

History, of course, shows how quickly “dangerous” can become a label for shutting someone down. Galileo was branded a heretic. Abolitionists and suffragists were denounced as radicals. And today, the same reaction plays out in uglier ways. Smear someone as a “Nazi,” and suddenly ordinary disagreement is recast as moral warfare. As Cambridge psychologist Leor Zmigrod has shown, once opponents are cast as monsters, our capacity to see them as human diminishes, and moral limits fall away.

Shielding people from discomfort doesn’t make them stronger—it robs them of the chance to practice the mental flexibility they need. At Ghent University, cognitive scientist Senne Braem has shown that when people are rewarded for switching between tasks, they later switch more easily. When switching is discouraged, they become less cognitively flexible. The same pattern emerges in groups. As legal scholar Cass Sunstein has argued in his book Going to Extremes, like-minded people who only talk to one another don’t drift toward moderation—they grow more extreme.

Even entire societies can bear these scars. Harvard economist Alberto Alesina showed that decades of socialist rule in East Germany left citizens more cautious, less entrepreneurial and slower to trust—habits of conformity that lingered long after the Berlin Wall came down. Institutions are no different. Without the stress of internal dissent, blind spots harden into dogma and capture by dominant factions becomes almost inevitable.

Listening to someone with an opposing perspective isn’t about conceding the point or winning the argument. It’s about keeping your mind flexible when every instinct says to shut down—or to strike back. In an age when AI systems are being trained on increasingly filtered datasets, baking blind spots into technology at scale, the human ability to stay open to challenge is more vital than ever. We can’t afford a generation that flinches at disagreement.

Eve’s lesson still holds. Reach for the difficult fruit—carefully, respectfully and with open eyes. The reward isn’t just what you learn; it’s who you become when you keep listening.