What Mill and Marcuse can teach us about Trump.

“Cancellation of the Liberal Creed”?

By John Tomasi

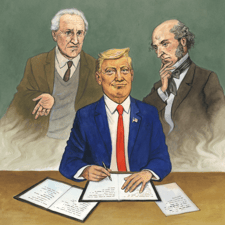

Illustration by Martin Hargreaves (used with permission).

Debates between dead philosophers sometimes illuminate events in our present-day world. I’d like to revisit one such debate — a dispute about the value of free expression and about the use of anti-democratic power in the name of reform, as it illuminates a basic choice facing university leaders today.

On one side, we find the great defender of free expression and political toleration, John Stuart Mill. In On Liberty (1859), Mill championed individuality, arguing that people should be free to live, act, and think the way they want, so long as they do not harm others. Mill worried about the “tyranny of the majority,” the tendency of human groupings to fall into the soft coercion of group-think.

Against this danger, Mill advocated toleration and free expression of dissenting opinions. In some cases, Mill argued, a majority view proves to be false. In others, the majority view needs supplementation from the dissenting view. Even if the majority view turns out to be true, people still need to consider criticisms of it, so that they can hold that truth in a lively way. In Mill’s lovely phrase: “He who knows only his own side of the case knows little of that.”

Mill did not coin the expression “a market-place of ideas.” But that image captures Mill’s view of an ideal community of knowledge-seekers. Truth is not a static achievement. Discovering and preserving knowledge requires discussion, examination and counter-examination. In short, the pursuit of knowledge requires the free and ongoing exchange of ideas.

In his 1965 essay “Repressive Tolerance,” the philosopher Herbert Marcuse provides a rejoinder to Mill’s argument. Marcuse begins by accepting Mill’s main argument [1]. (In philosophy, when a critic begins by granting your argument, you know you are in trouble). The free and open exchange of ideas can indeed lead a community toward greater understanding. However, Marcuse adds, whether or not toleration and free expression will actually have that effect depends on the preexisting structures of power.

As Marcuse puts it: “The function and value of tolerance depend on the equality prevalent in the society in which toleration is practiced” (p. 84). If power is held unequally, then the formal processes of free expression, instead of upending status-quo understandings in pursuit of truth, will simply reinforce those understandings. Just as some say “free trade” reproduces preexisting inequalities of economic power, Marcuse says “free speech” reproduces inequalities in social and cultural power.

To Marcuse, the inequalities of power within late-1960s capitalist societies were so great that formal processes of toleration and the putatively free exchange of ideas would repress those holding dissenting and politically radical views. Views from the political Right supporting the status quo — views expressed by those controlling the means of production, including sites of education and sources of media — would predictably dominate and defeat views expressed from the Left, which, on Marcuse’s reading, would always be weaker in a capitalist context. Further, Marcuse says, the machinery of free expression, such as “open debates,” would lend a veneer of justification to their results, even though those results were merely a reflection of the patterns of power that preexisted the discussion.

To counter these distortions of “pure toleration,” Marcuse advocated direct and muscular action against liberal norms. To liberate the minds of the young may require “apparently undemocratic means,” such as “the withdrawal of toleration of speech and assembly from groups and movements” which defend the (repressive) status quo (p. 100). These aggressive methods, sometimes including violence (p. 117), are a condition of free expression. There is a natural right of resistance for the oppressed “to use extra-legal means if the legal ones have proved to be inadequate” (p. 116). Marcuse writes:

“The restoration of freedom of thought may necessitate new and rigid restrictions on the teachings and practices in the educational institutions which, by their very methods and concepts, serve to enclose the mind within the established universe of discourse and behavior — thereby precluding a priori a rational evaluation of the alternatives.” (pp. 100-1)

In sum, Marcuse calls for the “cancellation of the liberal creed of free and equal discussion” (p. 106). If this seems anti-democratic, Marcuse disagrees: “The problem is not that of an educational dictatorship, but that of breaking the tyranny of public opinion and its makers in the closed society” (106).

To Marcuse, the inequalities of power within late-1960s capitalist societies were so great that formal processes of toleration and the putatively free exchange of ideas would repress those holding dissenting and politically radical views.

It’s easy to recognize patterns from this dispute between Mill and Marcuse as they have played out on our campuses in recent decades. Marcuse’s argument seems tailor-made for activist faculty and students who reject HxA’s conception of the university as a special kind of convening where students and professors come together in recognition of the partiality of their understanding and with the common aim of learning more, together.

Specifically, professors and students who have adopted illiberal (and sometimes extra-legal) tactics such as shouting-down speakers, launching cancellation mobs against those whose ideas they dislike, commandeering campus quads and taking over buildings, and shaming and even attacking students for their religious or political convictions take a different view of the university and of their role in it.

Rather than recognizing themselves as members of a community of imperfect learners, on certain issues they see themselves as set apart from the great project of learning and scholarly discourse. They are set apart precisely because, on certain topics, they believe their understanding already to be perfect.

The topics may vary — climate change, racial justice, gender ideology, or the conflict in the Middle East — but the pattern is notable: On such topics, campus activists do not seek to engage in discussion with people who think differently, seeking to persuade them by evidence or reason. Nor do they invite others to join them in exploring novel pathways of understanding old problems. Instead, their role is to organize and act on “truths” already known. They are intolerant not just of others but even within their own minds. In this, whether they are aware of it or not, the spirit of Marcuse is with them as they march.

All this is familiar enough. But consider: What if we take Marcuse seriously? What might a Marcusian say about the power imbalances on campus today? And how might Marcuse help us understand the early moves of President Trump’s administration on universities?

Recall, Mill thinks free speech and toleration enable humans to widen and deepen their understanding. But Marcuse points out, whether liberal norms will do that depends on the preexisting structures of power. If cultural power is imbalanced, then pure toleration will simply reproduce the dominant campus norms and paradigms. To break this “concreteness of oppression,” Marcuse advocates anti-democratic and quasi-legal counteractions.

Perhaps Marcuse lived in an era when it was plausible to declare that cultural power across American society was amassed on the Right. On campuses today, political power has become strongly imbalanced against the political Right. Indeed, among the growing class of scholar and student activists, campus power has even turned against liberal and scholarly ideals.

Donald Trump’s recent actions can be understood as a Marcusian reaction to the imbalance of power at our universities. Since President Trump’s second inauguration, we’ve seen a mix of actions, some of which demonstrate anti-liberal “withdrawal of toleration” from perceived enemies on campuses. These measures include threats of draconian budget cuts to curtail academic freedom and university self-governance, including forcing presidents to obey highly specific directives, such as placing government-specified departments into receivership; attempted blanket bans on teaching or research on topics deemed “divisive”; and nonresident graduate students arrested on the streets for what appear to be thought crimes. These measures are illiberal, undemocratic, and perhaps even illegal. They are also deeply Marcusean in spirit.

The topics may vary — climate change, racial justice, gender ideology, or the conflict in the Middle East — but the pattern is notable.

Yet we can expect, and are already seeing, this Trumpian onslaught to be countered by (equally) Marcusian and (equally) anti-liberal reactive forces, forces which in the decades before Trump had been gaining power. But if campus groups seek to defend the status quo, Marcuse has advice for the Trump administration. For, if the reformers of institutions “are blocked by organized repression and indoctrination, their reopening may require apparently undemocratic means. This would include the withdrawal of toleration of speech and assembly from groups and movements” (p. 100). But of course, the campus activists can read Marcuse too, so they can be expected to respond using all means of force or subterfuge available to them.

Thus, in one possible (near) future, our universities become a battleground between illiberal Trumpians on the Right and illiberal campus activists on the Left. It is a bleak picture.

But there is a more constructive way to respond to the Marcusian point about the significance of power imbalances.

Rather than withdrawing toleration from perceived enemies, we extend toleration in a principled way — much as Mill recommended. Seeing an imbalance of power, we don’t go on a violent, illiberal offensive, arrogantly seeking to destroy our foes at any cost and by any means.

Instead, we earnestly measure the imbalances of power that have arisen on our campuses, and we frankly name them. Then, instead of attacking, we reach out our hands to bring together presidents, professors, and students of good will, devising creative policies and reforms that might correct those imbalances within the boundaries of the law, and by strengthening rather than abandoning the norms of the scholarly profession. This future is possible. HxA stands ready to help.

For discussion of these topics, the author is grateful to David Estlund and Eric Torres.

References:

- ^ 1. Herbert Marcuse, “Repressive Tolerance,” in A Critique of Pure Tolerance, eds. Robert Paul Wolff, Barrington Moore Jr., and Herbert Marcuse (Boston: Beacon Press, 1969), 95–137.